In late 2016, a group of American diplomats in Cuba fell mysteriously ill, experiencing symptoms that ranged from headaches, hearing and memory loss, nausea, fatigue, and even brain damage. This mysterious collection of symptoms is referred to as “Havana Syndrome,” and there are a lot of theories as to possible causes—including neurotoxins from insecticides, and even a sonic attack.

The sonic attack theory emerged because multiple diplomats recorded an eerie, high-pitched sound the night their symptoms appeared, and they assumed they were hearing a sonic weapon. But last year, UC Berkeley graduate student Alexander Stubbs, along with Fernando Montealegre-Z of University of Lincoln, listened to the diplomats’ sound recordings—and after thorough investigation, discovered that the sounds actually matched the chirp of Anurogryllus celerinictus, the Indies short-tailed cricket.

“The call of this cricket does not cause people to have adverse physical reactions,” Stubbs said in a phone interview last year. “I don’t want anyone to potentially hear that species of insect and think they or their family could be at risk due to that sound.”

Knowing that the sounds the diplomats heard were crickets, Stubbs says another explanation worth considering is that Havana Syndrome may be a case of mass hysteria, where the diplomats’ ailments are psychosomatic and they imagined themselves sick after hearing the crickets’ call.

“In my opinion, the sonic attack story seems to be a media and government narrative, not informed by rational science,” Stubbs says. “Once you break the link between the sound and the symptoms, it starts to seem less likely that the diplomats were victims of a nefarious attack.”

Of course, Stubbs says that medical diagnoses should be left to public health experts (not him), and further investigation is necessary to determine what really happened in Havana. However: “It’s totally possible that something weird is going on here,” Stubbs says. “For all I know, there was an attack. But the fact is, there’s a whole list of crazy possibilities with no proof in the public domain.”

It’s true: Despite all the chatter in the media and among politicians, we know a whole lot of nothing about why these diplomats got sick.

But we do know that this isn’t the first time mass hysteria and bugs have been caught in the same web of mystery.

For centuries, mysterious insect-related incidents have led doctors to dole out theories saying that people were imagining their sicknesses, and this was often accepted as fact because there were no other explanations.

Below you’ll find a collection of creepy crawly cases of yore, with descriptions of wickedly weird sicknesses that allow you to put yourself into the shoes of past victims and decide what you believe. Were these people afflicted by something real, or were they simply… bugging out?

The Sickness

It’s the late 1300s in Italy. You’ve just woken up from a deep sleep to find you can barely breathe. Your muscles are rigid, you’re crying uncontrollably, and even worse, you have priapism—an extremely painful boner. (Mama mia!)

Fear wells up in your chest. You know what this is. It happened to your neighbor Gianna last week (everything except the boner part), and her neighbors’ neighbors. It’s all everyone has been talking about for months, and your time has finally come.

Yes: A tarantula has allegedly bitten you and now you’re the victim of tarantism, a condition that can also result in tremors, hyperactivity, sweating, and in its most vicious rendering: fainting spells, delirium, and even convulsions.

Your friends told you what you have to do for treatment, and you know you must, but it’s going to be painful. Probably not as painful as your boner, but painful, all the same.

There’s no time to wait. You must cure yourself: So you start dancing like you’ve never danced before, exorcising what ails you by exercising your right to shake what your mama gave you. As you shimmy and undulate, you can feel the sickness dripping out of you through buckets of sweat, and after three straight days of perfecting your Dougie (a signature move that won’t be properly appreciated for centuries), you collapse—exhausted, but finally “cured.”

The Explanation

A lot of people in the Middle Ages thought they’d been bitten by tarantulas. Tarantism is thought to have been named after Taranto, Italy, where an epidemic of tarantism occurred in 1370 before crawling to Croatia, Spain, and other areas of the Mediterranean.

Why tarantulas (Lycosa tarentula) were the spiders blamed for the condition remains a mystery, mostly because they’re a species that rarely comes in contact with humans, and their bites are known to only cause an itty bit of pain and swelling. Some theorize that the actual culprit could have been Latrodectus—a spider whose bite can cause pain, muscle rigidity, vomiting and sweating.

The only cure for tarantism was thought to be prolonged, strenuous dancing to uptempo beats. Municipalities would hire musicians to work in shifts, playing music for up to four straight days so that victims could get their groove on.

Victims of a Latrodectus bite might also move constantly in response to the neurotoxin in the spider’s venom, so in the case of tarantism, it may have been true that dancing helped alleviate this symptom.

Regardless of what caused the condition, the hype about tarantism paired with public dancing spectacles are thought to have freaked out the locals so much that mass hysteria ensued. While some may have been bitten by spiders, it is widely assumed today that the majority of these cases were psychosomatic.

Any excuse to get jiggy with it, I guess.

Source: Medical and Veterinary Entomology

The Sickness

It’s June of 1962 and you’re putting in your usual hours at the textile mill. You wish you were listening to the Beach Boys or playing with your collection of elephant trolls, but instead, you’re spinning nylon and polyester into yarn, then putting it on the bobbin. Yarn. Bobbin. Yarn. Bobbin. You watch it spin round to a beautiful oblivion. “I just want to achieve my childhood dream of being a famous abstract painter,” you say to yourself wistfully, then let your melancholy get the best of you. “But I’ve got time,” you lie to yourself once more. Just another normal day at the office. Yarn. Bobbin. Yarn.

That’s when you start to feel like you’re gonna vomit. You think it’s the two week old lamb leftovers you just ate, but when a severe rash starts to spread across your body, you know it’s something more. Panicked, you go straight to the infirmary, but they can’t determine the cause. It’s only getting worse.

“I didn’t even get the chance to cut off my ear,” you think to yourself as you drive home, surely on the brink of death. You manage to make it to the next day, and receive word that several women and at least two men reported that they were experiencing the same symptoms. Frustrated by the by the doctors inability to drawn definite conclusions, you and the other workers take it upon yourselves to determine the cause of your fate: Surely this is all because of a bug infested fabric shipment that came in from England, and thusly, you and your coworkers have been bitten and therefore infected with a horrible disease-ish thing!

The Explanation

This mysterious condition would eventually became known as the June Bug Epidemic, not because it has anything to do with real Junebugs or Phyllophaga, the genus of totally harmless, totally stupid beetles that love to fly aimlessly into windows and your face—but merely because the incident occurred in June.

Over the next week, 62 of 900 mill workers claimed they had been bitten and were overcome with the illness, resulting in them either being absent from work or receiving medical treatment. At the epidemic’s peak, the mill briefly closed to see if these mysterious bugs could be located. After a rigorous search by the mill’s health officials and members of the Communicable Disease Center of Atlanta, only two biting bugs were found in the entire plant.

Local physicians, management and other health authorities all agreed that it was a case of mass hysteria. After all, there was a lot of anxiety at the plant, and all of the symptoms of the alleged bug bites were symptoms that also resulted from exposure to high levels of stress.

The psychosomatic theory was floated to the workers, who staunchly disagreed with the diagnosis. Regardless, the owners of the plant had it sprayed for insects, mostly to make the workers feel safe, and following June, no more incidents were reported.

Sources: Emotional Contagion, the Madness of Crowds, Mass Hysteria, and Mass Sociogenic Illness, Somatoform Epidemics as Emergent Collective Behavior, Hysterical Contagion, Textile Mill Workers, Introduction to Collective Behavior and Collective Action

The Sickness

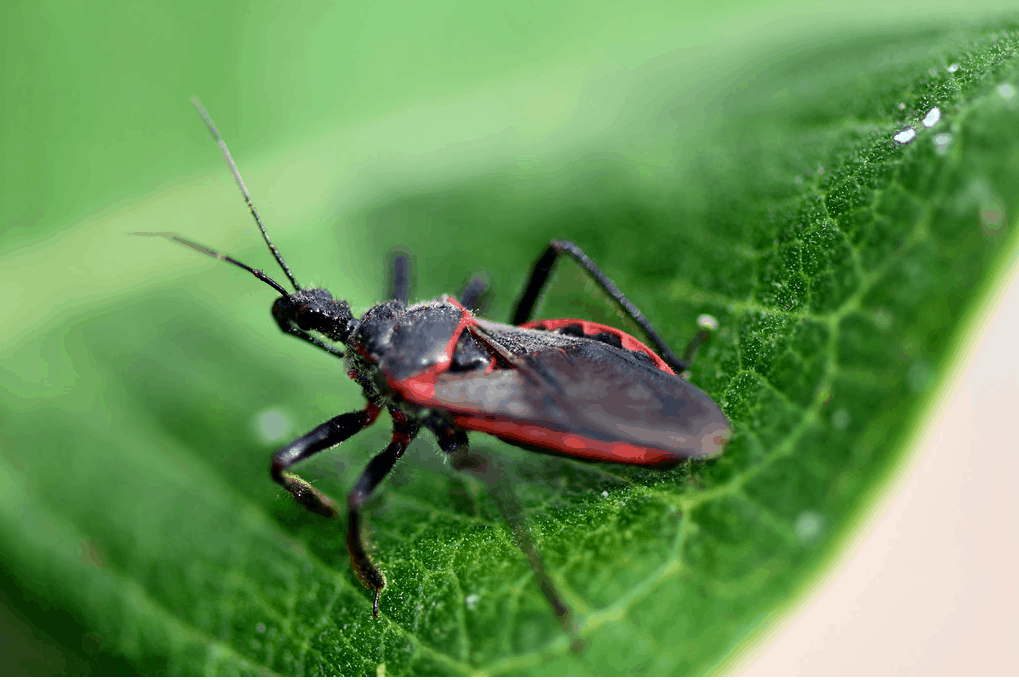

It’s the turn of 20th century in our nation’s capital and the living is easy. You just got one of those newfangled typewriter machines and a telephone, so you’re the envy of every D.C. businessman on the busy block. It’s 7:00 AM and you’re sipping hot coffee at the breakfast nook when a Washington Post headline catches your attention: “Bite of a strange bug,” written by journalist James F. McElhone. As your eyes crawl the page, you read that an unusually high number of people were admitted to the Washington City Emergency Hospital for insect bites, and that “several victims” “woke up to find both eyes nearly closed by the swelling,” that they had been “badly poisoned,” and that “the matter is beginning to interest physicians.”

You’re a little irked but otherwise distracted by your very important and official business affairs, so you think nothing of it until you see another strange bug story published nine days later in the New York Times. And another in the Boston Daily Globe. And then a follow-up in the Washington Post. And then another story. And another. Papers across the country are reporting on a bug that has apparently rapidly multiplied and is biting the faces of people as they sleep, with a special taste for victim’s mouths—a kissing bug.

On your way out the door one Monday morning, you take a look in the hallway mirror to adjust your tie. That’s when you see your lips—bloated like a pair of beached whales on the brink of combustion, now colored a dark scarlet purple, presumably from blood or infection.

You notice there are little red marks around your mouth and suddenly become acutely aware of how they’re beginning to ache. You lean in closer and notice some small red marks on the side of your face. WTF.

You run to your pristinely-made bed, throw back the covers, and see a dead bug. You have no idea what the kissing bug looks like because news reports of the bug’s actual anatomy were vague at best, so you immediately assume that must be the culprit.

Panicked, you run screaming from the room and rush to your brand new telephone, already feeling your eyes swelling shut as the poison sets in. It’s hard for you to see the dial and your sweaty palms cause you to drop the phone a few times before you can dial the number.

“Hello, is this the Washington Post?” you croak into the receiver.

The doctor can wait.

The Explanation

A century later, the Kissing Bug epidemic of 1899, in part, remains unsolved, but many experts agree that the majority of reported maladies were likely caused by the imagination.

Triatominae, also known as kissing, assassin or vampire bugs, do actually exist. They’re a subfamily of insects known for sucking the blood of mammals while they’re asleep, and to add insult to injury, when they’re finished, they poop on their victims. (Every famous criminal needs a signature move, I suppose.) It’s also true that they can carry Chagas disease aka American trypanosomiasis, which can cause symptoms such as fever, headaches, and swelling at the bite site. In serious cases, 10-30 years post-infection, some can suffer from an enlarged colon and esophagus, or even heart failure.

Usually found in tropical regions, it would have been unlikely that the United States would have been suddenly infested with kissing bugs. While Triatominae have been found in southern states, most of those discovered there don’t carry the Trypanosoma parasite and aren’t known to target humans as much as the kissing bugs who are native to Mexico, Central and South America.

While early reports from entomologists identified some of the bugs in question as being members of the Reduviid family—of which the kissing bug is a part—many victims sent in mosquitoes, houseflies, bees, beetles, and even butterflies, thinking they were the culprits.

So it came as a surprise to experts when a 33-year-old woman in Chicago died mysteriously and the only doctor who was able to examine her wrote on her death certificate: “Chief and determining cause of death, sting of kissing bug. Consecutive and contributory cause: tonsillitis.”

At this, medical experts wanted to look deeper into the diagnosis, but by the time they were able to gain access to the woman’s body, she had already been embalmed, so they couldn’t confirm her cause of death.

Regardless, journalists seemed to be set on the story of a disease-ridden insect, so newspapers printed stories with headlines like, “Cause of Death a Kissing Bug,” before there could be any medical consensus.

Because of this, experts have largely determined that the condition many people were suffering from was mass hysteria… and that newspapers were the main carriers of said hysterics.

As entomologist Leeland Howard wrote in the November 1899 issue of Popular Science Monthly, the kissing bug epidemic was largely a “newspaper epidemic, for every insect bite where the biter was not at once recognized was attributed to the popular and somewhat mysterious creature.”

“With nervous and excitable individuals the symptoms of any skin puncture become exaggerated not only in the mind of the individual but in their actual characteristics,” Howard writes, even comparing the kissing bug epidemic to tarantulism. “And this is the result of the hysterical wave, if it may be so termed.”

Sources: Panic Attacks: Media Manipulation and Mass Delusion, The 1899 United States Kissing Bug Epidemic, The Kissing Bug Craze

The Sickness

It’s the late 1970s in Vietnam, and you’re bent over planting rice in the paddy fields, moving much slower than you’d prefer. At 65, your bod ain’t what it used to be, and you watch as your neighbor and lifelong frenemy, Dong, five years your junior, gives you a smug look and a wink as he plants with ease. “Classic Dong,” you say under your breath, seething.

It starts to rain. You adjust the fabric strap on your cone hat and peer out over the field, noticing that the moisture dripping from your hat’s brim is yellow. You hold out your hand to catch some droplets and they roll off your palm like oil, then you notice that the rain smells like gunpowder.

Immediately, people start to panic and run fervently for cover. Dong is screaming like a little girl and yells, “Chemical weapons!” as he slips and falls into the sloppy wetness of the field.

You’re very worried now, but also, “HAHA Dong.” He can’t be right, could he? The war is over. Isn’t it?

That’s when your skin starts to feel hot and the pho you had for lunch churns in your stomach. You heart starts beating fast and you bend over to vomit. When you’ve emptied what feels like all of the contents of your body, you start to run for home but it’s hard to see: your vision is blurring, and your skin has gone from feeling hot to on fire. Fear swirls around your head like a menacing swarm of insects as you realize Dong may be right.

“I’ll never make it home,” you think. “I’ll never make it to 66.”

The Explanation

After the end of the Vietnam War, a mysterious yellow substance—which people called “yellow rain”—fell from the sky and allegedly made Hmong refugees in Vietnam dramatically ill. In addition to the horrors of burning skin, puking, and blindness, there were also reports of seizures, massive hemorrhaging, skin turning black from subcutaneous bleeding, and even death.

The yellow rain sent people into a panic, and then-U.S. Secretary of State Alexander Haig accused the Soviet Union and its allies of using “lethal chemical weapons,” claiming that the rain was composed of mycotoxins—poisonous substances synthesized by fungi.

Further investigations by U.S. chemical warfare experts, however, suggested something different. The symptoms reported by Hmong and Cambodian refugees didn’t match up with effects from known chemical warfare agents, but they did match the effects of exposure to trichothecene mycotoxins: natural poisons that grow on some species of corn, wheat, millet, and other grains.

Known to exist in tropical countries like India and Thailand, these mycotoxins were likely present in Laos and Cambodia. Experts theorize that the trichothecene poisoning came from food contamination, a hypothesis supported by the fact that an alleged “yellow rain victim” had trichothecenes highly concentrated in his stomach. Also, the symptoms of yellow rain were reported during the dry season in Southeast Asia, when food supplies were low and the risk of eating moldy grains were highest.

The plot thickened as scientists discovered that yellow rain had pollen from plants indigenous to Southeast Asia—and the pollen in the samples matched another well-known substance: Bee poop.

Entomologists and bee specialists noted that Southeast Asian honey bees fly together en masse and can create showers of pollen-rich feces that cover acres of land with yellow spots. One Yale entomologist said that when he observed the phenomenon himself, the bees flew at about 50 feet above ground at 20 mph—and were very difficult to see.

Those who believed the bee hypothesis thought that the reports of Hmong refugee symptoms had been embellished by U.S. officials looking for someone to blame. This led to more illnesses via “mass suggestion.”

According to the reports, the symptoms varied so widely between each refugee that pointing the finger at one chemical seemed suspect. For instance, eight percent had bloody vomiting, 10 percent had bloody diarrhea, 21 percent had rashes or blisters, and five of the victims had a full constellation of symptoms. If the agent was designed in a lab and mass distributed, it would be hard to explain why the symptoms were so dramatically different between each person.

Early interviews with victims and witnesses of the “attack” were all based on first-hand accounts, and follow-up interviews with the same people presented inconsistencies and holes in their original stories. Over 200 attacks had supposedly taken place in the Phu Bia vicinity, but a Hmong resistance leader told the State-Defense team that there was never an attack and that it was all rumor.

Some scientists and academics hypothesized that it was all just coincidence: Bees just happened to be crapping on villagers at a time when they were eating moldy food and war-anxiety was high, and it created a buzz that resulted in mass hysteria about chemical warfare.

Despite lack of conclusive evidence, the U.S. government never retracted their claims that it was chemical warfare, and even publicly speculated that pollen had been added to the chemical agent in order to make the substance easily inhaled and retained in the human body.

What we know for sure is that some people did suffer from illnesses that proved at times to be fatal, and that what exactly caused said illnesses remain inconclusive to this day.

We also know that a theory of evil bee poop seems like the basis of a terribly bad dream or a really amazing sci-fi flick.

Sources: The “Yellow Rain” Controversy: Lessons for Arms Control Compliance, Yellow Rain in Asia, The Mystery of Yellow Rain, Was This Mysterious “Yellow Rain” a Chemical Weapon or Bee Poop?