Last year, I made my first trek to Willow Creek, California, a town known as the “Bigfoot capital of the world.” Today marks the 59th annual Bigfoot Daze Festival, and while I won’t be there this year, I encourage you to check out this collection of letters from yours truly chronicling my visit. I write all about the town’s history, the mystery, and what’s it like to get lost in the Bigfoot craze—one giant step at a time.

These letters were originally published in California magazine, but I’m running them here on my blog for your viewing pleasure (with a bonus of extra photos not included in the California mag story). Enjoy.

Friday, August 31, 2018

11:00pm

It’s a cool summer night in Willow Creek, California, and I just chose to spend three hours of it in a hot, humid hotel room, holding the hand of a Bigfoot. Well, a Bigfoot’s hand cast, anyway.

Daryl Owen, a white-haired man with a big grin and a small gap in his teeth, invited me over to show off his Bigfoot evidence. I met him outside the Bigfoot Motel just as I arrived. He was explaining to the front desk clerk that a news team had followed him and his crew, known as the NorCal Squatchers, to Willow Creek in a van, and that it was “so hard being famous.” He had been on Ancient Mysteries after all, and Good Day Sacramento, he said. I was standing next to Sasquatch royalty.

“I wanna say we’re pretty famous. I mean, we’re pretty good,” Owen told me in his motel room. “We’ve been on TV a couple of times. I’ve been on a TV show. People know our names. They know we’re NorCal Squatchers. They drive up beside our truck and give us the thumbs up, or the bird, or whatever, but… we’re well known.”

He pulled the cast of a Bigfoot hand from a military spec storage container, cradled the lumpy mass of plaster in his arms and called it his baby. Owen said that when he died, he’d pass it on to his son-in-law Russell Stater, who was seated on one of the beds, while Owen’s daughter Taryn looked on silently from a seat in the corner of the room. These three were the NorCal Squatchers from Sacramento, and just like me, they were here for the Bigfoot Daze Festival, Willow Creek’s annual summer event where people from all over come together to celebrate Sasquatch.

You see, Willow Creek is famous for Bigfoot. This small town in Humboldt County refers to itself as the “Bigfoot Capital of the World” because it’s where so many famous (and not so famous) Bigfoot researchers have stayed during their quests for truth. Which I guess, includes me now. After discovering Grover Krantz, the UC Berkeley-trained anthropologist known for being the first leading “Bigfoot scientist,” I’ve become obsessed with the Sasquatch phenomenon and the people who keep it alive, enough to drive 300 miles north from Berkeley to this middle-of-nowhere town. I may not be totally convinced that Bigfoot is real, but damn, am I glad that Bigfoot researchers exist.

Owen rattled off what seemed like a thousand details about the pursuit of Bigfoot in that motel room, bizarre and unsettling stories tumbling from his mouth like skeletons from the closet. His eyes danced as he described encounters from three decades back, the memories distinct like fresh monster tracks in the mud. I couldn’t tell what he liked more—watching me scribble his words down frantically, or seeing me pause as my mouth fell open.

In one story, he and his friend Scott Herriot ventured up a mountain in Klamath, California, came across a log that had fallen, and saw a pair of shining eyes beneath it.

Owen moved quickly to the right of the log and saw that about three meters away there loomed a hairy, beige beast, eight feet tall, staring down at the log as if to guard it. It turned its face slowly to look at Owen, and according to him, its gaze seemed to “stall time.”

“I wet my pants. I mean, I lost it,” Owen told me. “I dropped the camera and I stood there and cried. I mean, it was brutal. It was just more fear than you could possibly imagine.”

But not enough fear to change his ways.

Owen continued the search for Sasquatch, even when someone painted “Hoaxter” on his garage door in red paint, even when he lost friends, even when his wife divorced him, even when he allegedly received gag orders from government agencies and educational institutions telling him to stop the search. (He refused to go on the record about who these organizations were.)

“Some say Bigfoot is bad luck,” Owen said. “I believe it.”

But I don’t buy it.

As a reporter searching for Sasquatch seekers, I’d say Bigfoot has thus far brought nothing but good luck to me. I’ve hit the jackpot. (That is, if you don’t count this motel bed, which feels like a sofa cushion with broken springs. I chose the Bigfoot Motel for the thrill, not the YELP ratings, okay?)

Oh, well. Who needs sleep? This whole night already feels like a crazy dream.

Friday, September 1, 2018

11:45pm

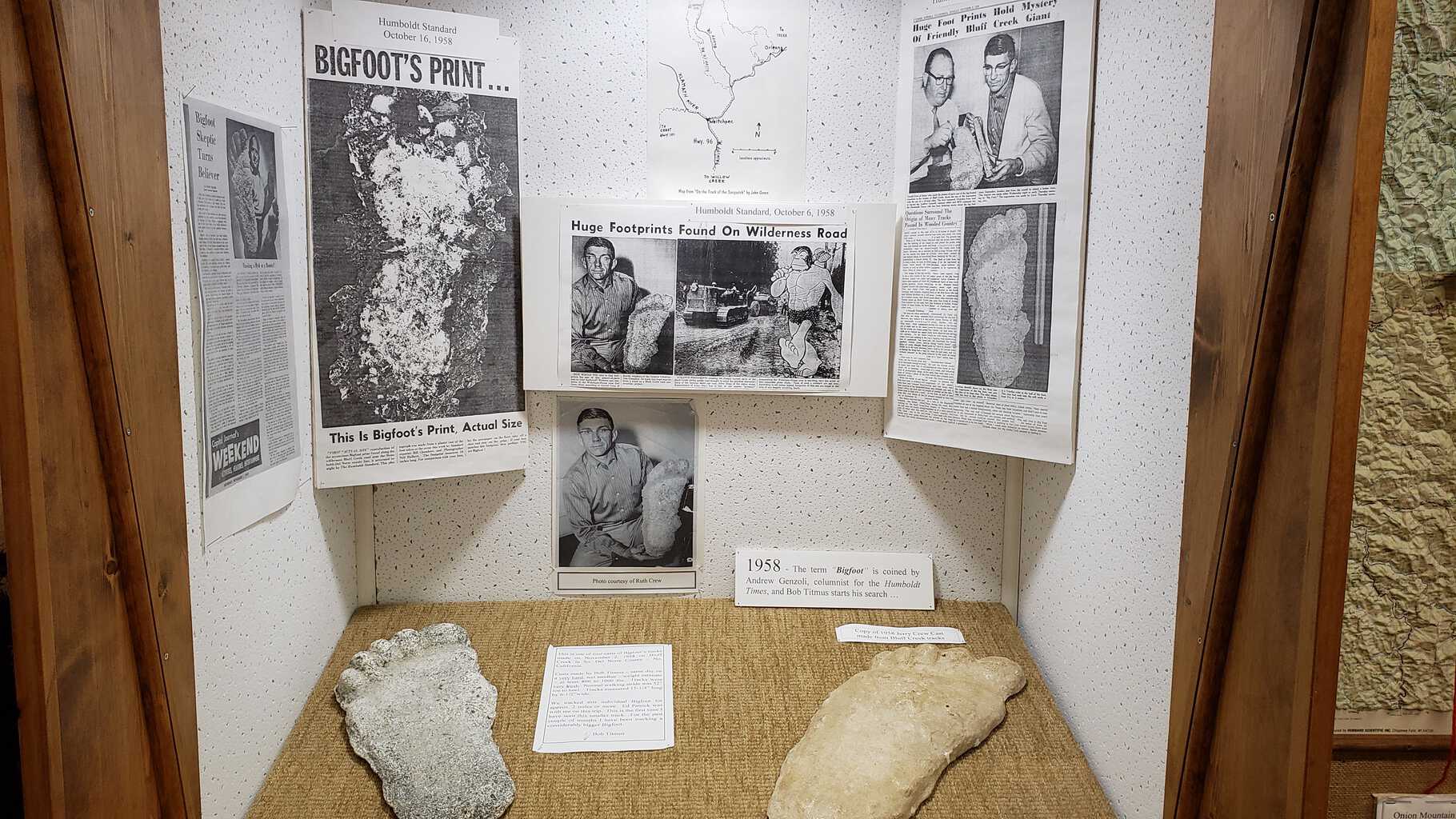

P.S. All the hype around Bigfoot in Willow Creek started with an average Joe—or rather, an average Gerald “Jerry” Crew. He was a construction worker tasked with bulldozing wilderness to make way for new roads in Bluff Creek—a heavily forested region 40 miles north of Willow Creek on Highway 96. One August morning in 1958, Crew and his crew returned to the construction site to find 16-inch, human-esque footprints along the roadside and around the equipment; some creature had been all up in the construction machinery’s business.

Scared witless, 15 of the men quit. But this Crew guy was curious.

He cut a footprint outline out of cardboard, tracked down the local tracker and taxidermist, Bob Titmus, and asked if he knew what creature left such a massive impression.

After careful consideration, Titmus was stumped. He’d never seen a print like it. All he could offer Crew was some plaster and casting instructions.

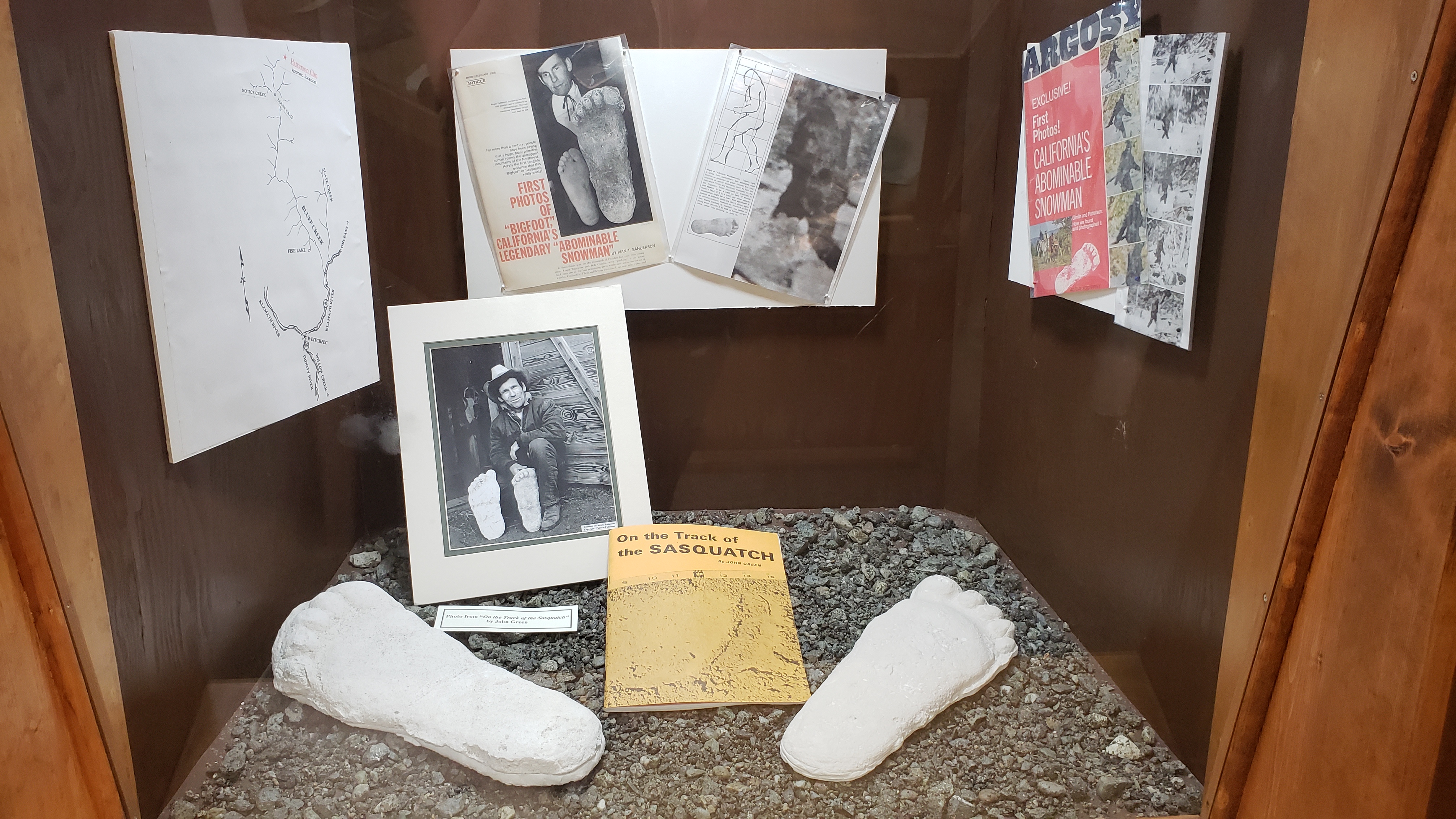

Crew went back to the site, made a cast of the print, then schlepped the 16-inch lump of plaster into the offices of the Humboldt Times. BOOM! The next day there was a cover story with “Big Foot” in the headline, complete with a photo of Crew posing with his giant foot cast, smiling only with his eyes. This sparked a wildfire in the press that chased the name Bigfoot out of the forest and into the mouths of citizens across America.

Could Bigfoot be real? And, I wonder—could he be looking for a job in construction?

Zoologist Ivan Sanderson examined the casts, concluding that an unrecognized animal was indeed responsible for the prints, as did primatologist John Napier who, in his 1973 book Bigfoot: The Yeti and Sasquatch in Myth and Reality, wrote: “One is forced to conclude that a manlike life-form of gigantic proportions is living at the present time in the wild areas of the northwestern United States and British Columbia.”

Years later in 1967, two men named Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin would film a Bigfoot with pendulous breasts trudging through Bluff Creek—peeking over her shoulder like she had a silly little secret to tell before disappearing into the woods. This Bigfoot came to be called Patty, and this famous film, aptly titled the “Patterson-Gimlin film,” has gone down in history as the most definitive evidence of Sasquatch’s existence—even though many think it’s a hoax.

Grover Krantz, for example, deemed the film a big fake when he first saw it, calling it just “a guy in a gorilla suit.” After closer examination of the film, however, he ended up advocating for its authenticity and maintained his position until his death. According to Krantz, no human could move the way Patty moved. Even after a retired Pepsi bottler from Yakima, Washington named Bob Heironimous told National Geographic that he was actually the guy in the suit, believers called Heironimous a liar, saying that his only aim was to discredit Bigfooters, that all he wanted was the fame.

Real or hoax, Crew’s big plaster foot cast (and even Patty’s big boobs) might as well have been made from dough—as in cash money—because Bigfoot tourism stimulates the town’s economy. Willow Creek is the first larger town one comes to when leaving the wilderness up north, and it’s the place where Sasquatch seekers historically have hung their hats after a long weekend of searching.

The Willow Creek Chamber of Commerce hasn’t tracked stats on how much money Bigfoot tourism pulls in, according to Anne Keaney, the Chamber’s executive director. But Terry Castner, treasurer for the Willow Creek China-Flat museum, known for its Bigfoot exhibit, estimates that the museum’s gift shop generates $300-500 every day it’s open—from Bigfoot merch alone. I don’t know much about small town commerce, but for such a tiny museum in the middle of nowhere, a few hundred bucks a day sounds like an impressive chunk of change.

“Bigfoot tourism keeps the museum alive. It keeps Willow Creek shops alive. Sasquatch tourists eat at the restaurants, they buy gas, and if something is wrong with their car, they go to the hardware store,” Castner told me over the phone. “During the Bigfoot Daze festival, we have 150-200 people backed up out the door, waiting in line to get in.”

Rather than Jerry Crew or the famous strutting Patty, it seems like it’s the curious visitors who make Willow Creek the “Bigfoot capital.”

It was why I showed up, after all. I came seeking Squatchers and I found them.

Saturday, September 1, 2018

6:00pm

Maybe I’m being hypercritical, but you’d think a Bigfoot Daze Festival would be more, I don’t know… Bigfooty.

The festival kicked off with a “Superhero Bigfoot” themed parade in downtown Willow Creek along Highway 299, but most of those participating didn’t adhere to the theme. The parade just seemed like a chance for people to ride their trucks down the street and smile. Granted, those who committed to Bigfoot did a good job. One float had six women in capes riding exercise bikes alongside a masked Sasquatch, pumping their legs to booming music and waving to the crowd like maniacs. Gotta stay fit to rough it in the wilderness, I guess.

After the parade, the festival continued at Veterans Park, a grassy area with some swing sets and a baseball field off to the side. There were about a thousand people there to celebrate Sasquatch, but Sasquatch activities were in short supply.

I enjoyed the howling contest, where children and adults roared wildly into a microphone for the fame and glory of being recognized for the best Sasquatch yell, but that was about it for Bigfoot-related entertainment.

Most tents and trucks were selling normal festival food like hamburgers, ice-cream, and corn on the cob—all delicious menu items—but none cleverly named after any mythical beasts. The only vendors there that had anything to do with Sasquatch were the NorCal Squatchers and a store from out of town called Supernatural Shack; they sold Sasquatch keychains and various colors of putty with labels like “Bigfoot Poop” and “Alien Slime.”

Not that I didn’t enjoy the festival’s watermelon eating contest or the casual pick-up ball game, but come on! I was there for the Bigfoot Daze Festival, and I expected it to deliver. I wasn’t Bigfoot dazed, but I was confused.

I asked around, desperate for more history, intrigue, story. The festival itself wasn’t that Squatchy, but perhaps the residents would be.

“I definitely believe [Bigfoot] exists,” said Troy Luhnow, a fire prevention captain who has worked for the U.S. Forest Service for 13 years. “Too many things have been told to me, stories passed down. Too many areas where sightings have been happening … Large rocks being thrown [in campsites] that were too big for people to probably throw.”

I asked if it was weird not to believe in Bigfoot if you live in Willow Creek, and Luhnow said nah.

“I don’t think people would judge you either way, to be honest,” Luhnow said. “People are pretty open-minded here. And if anybody brought it up to the U.S. Forest Service, “I think we’d look into it, just out of curiosity more than anything.”

I didn’t encounter anyone who had sightings of their own, but others I asked about Bigfoot said they believed because of sounds they heard in the night and tales from their friends and neighbors.

“If you don’t want to believe in Bigfoot, that’s your choice,” said Mike Grable, a retiree who has lived in Willow Creek with his wife Wendy for the last 11 years. “But I believe. I haven’t seen him exactly, but I’ve heard him close to, or near my house, howling. There’s not a man alive that I know who could make a sound like that. It put chills on me when I heard.”

Despite said chilling tales, other locals remain unconvinced.

“[Bigfoot] has a good commercial value and it makes for good tourism, but if you go to Washington D.C., and go to the Smithsonian—you can see whole dinosaurs put together! Every backbone! Everything! All of them, millions of years old. And there’s not one Bigfoot bone,” said Brian Trout, a farmer who lives just outside of town. “You give me one bone, I’ll change my opinion. I believe in science, absolutely.”

Though completely anti-Bigfoot, Trout admits that while working in the woods all over the Pacific Northwest for the last decade, he’s had some questionable encounters with species he couldn’t identify.

One night, he was driving up a mountain with a friend when a brown, fuzzy animal resembling a creature from the movie Gremlins hopped out in front of his vehicle.

“It looked like a Mogwai, with the little ears and big eyes, but it had a rat tail, like a skin tail … and it jumped like a skunk across the road. I mean, I don’t know if it was a baby fisher [a fuzzy rodent-like animal native to North America] … but fishers don’t have rattails!” he said.

He explained that even though he couldn’t make sense of what he had seen, he eventually got the courage to tell his friends about it. But they didn’t believe him until they saw it themselves, under a bench in someone’s backyard, staring up at them with big, cute eyes.

“And they were like, ‘We saw it! It’s exactly as you said,’” Trout said. “At least they know I didn’t lie.”

As someone who has read and listened to quite a few Sasquatch accounts lately, I gotta say that the formula of Trout’s story was identical to those who have had Bigfoot sightings, even if what he was describing was a baby Mogwai.

He went through what I’d like to call The Five Stages of Sasquatch Belief: (1) surprise, (2) denial, (3) bargaining, (4) fear of social suicide, and (5) telling everybody anyway.

I actually went through the five stages myself when I had my own encounter today… with a Bigfoot Burger.

It happened in broad daylight. Right on HWY 299 at the Early Bird restaurant in the middle of the afternoon. That’s when I saw it. Everything I’m about to tell you is true.

(1) I was surprised by how perfectly buttered and toasted the 10-inch bun was, how they managed to mold the dough into adorable toe-lumps on the end. (2) I attempted to deny how delicious the pound of hamburger, bacon, and cheese was so I wouldn’t eat the whole thing (3), I tried to bargain with the guy behind the counter for extra fries. (4) I feared my boyfriend would leave me after I returned from Willow Creek 20 pounds heavier. (5) And now, despite myself, I’m telling you about the burger anyway, even though I know you could never understand until you experience it yourself.

I hope someday you do. Because at least then, you’ll trust me.

You’ll know I didn’t lie.

Sunday, September 2, 2018

5:00pm

When some people look at Willow Creek, all they see is Bigfoot. It’s a tourist trap, and the town has worked very hard to make it so.

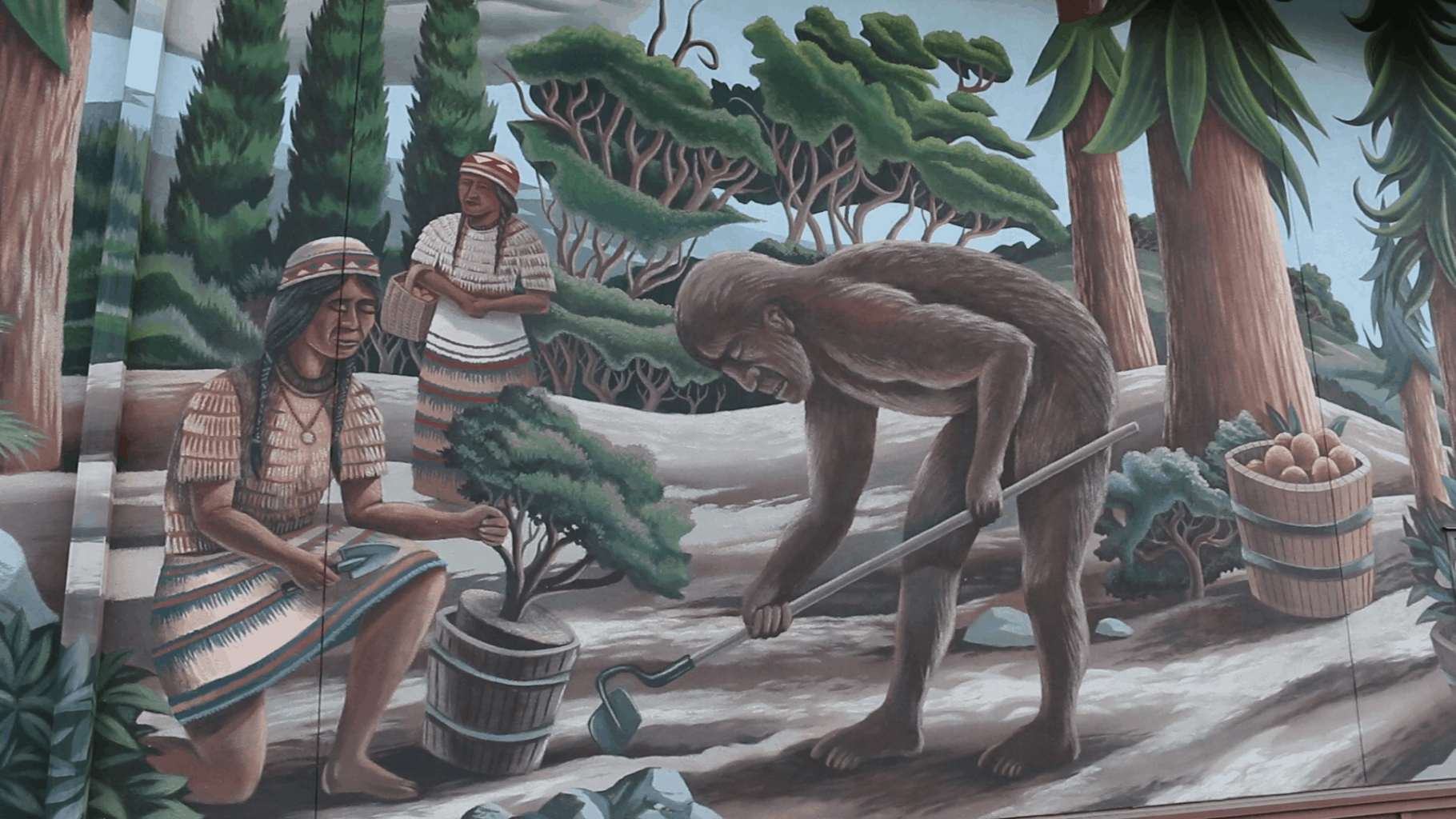

There’s the Bigfoot Motel, Bigfoot Steakhouse, Bigfoot Rafting, Bigfoot Books, and Bigfoot Podiatry. There’s Bigfoot statues on every corner, and massive murals depicting Bigfoot working in harmony with the Native Americans and cowboys, or standing in front of a mountain. There’s Bigfoot Avenue and Bigfoot Burgers.

Liberace was subtler.

But is there more to Willow Creek than just Bigfoot? I wanted to know.

So I checked out Willow Creek’s China-Flat Museum, known far and wide for its extensive Bigfoot exhibit, to see if anything other than big, hairy beasts consumed the town or shaped its history.

The answer is: Not really.

Or if there is more to Willow Creek, that information isn’t easily available to the public.

The museum was full of glass cases like you’d see at a jewelry store, filled with eclectic collections of ole-timey items strewn about without labels: Indian cooking rocks, a .22 Special, river otter and cougar hides, arrows, Humboldt beer bottles, a JELLO mold, old copies of Heidi and Tom Sawyer, and an inordinate amount of chamber pots.

It was like an antique thrift store where you couldn’t actually buy anything (and probably wouldn’t want to).

I asked museum docent and former board member Penny Chastain if Willow Creek had any other big historical claims to fame outside of Bigfoot, and it didn’t seem like it. Items that had descriptions were from neighboring cities like Arcata and the larger Humboldt county area.

In a back room of the museum was the Bigfoot exhibit, which, Chastain said, is what 95 percent of visitors come to see. (Surprising, I know, considering the extraordinary chamber pot collection.) The Bigfoot space was much more carefully curated, with neat labels, soft-lighting, and a crapload of information.

I was sad that I arrived too late to meet Al Hodgson, elder statesman and historian of Willow Creek who died just months prior to my visit, in April of 2018. According to the townsfolk I met at the festival, he was not only devoted to the community as a store owner and charter member of the fire department, but he also volunteered at the museum and was largely responsible for shaping the Bigfoot exhibit into what it is today. Hodgson knew Jerry Crew personally and was the man that Patterson and Gimlin came to the day after they filmed Patty trudging through the woods. The guy was legend, and in that museum, I was observing his handiwork.

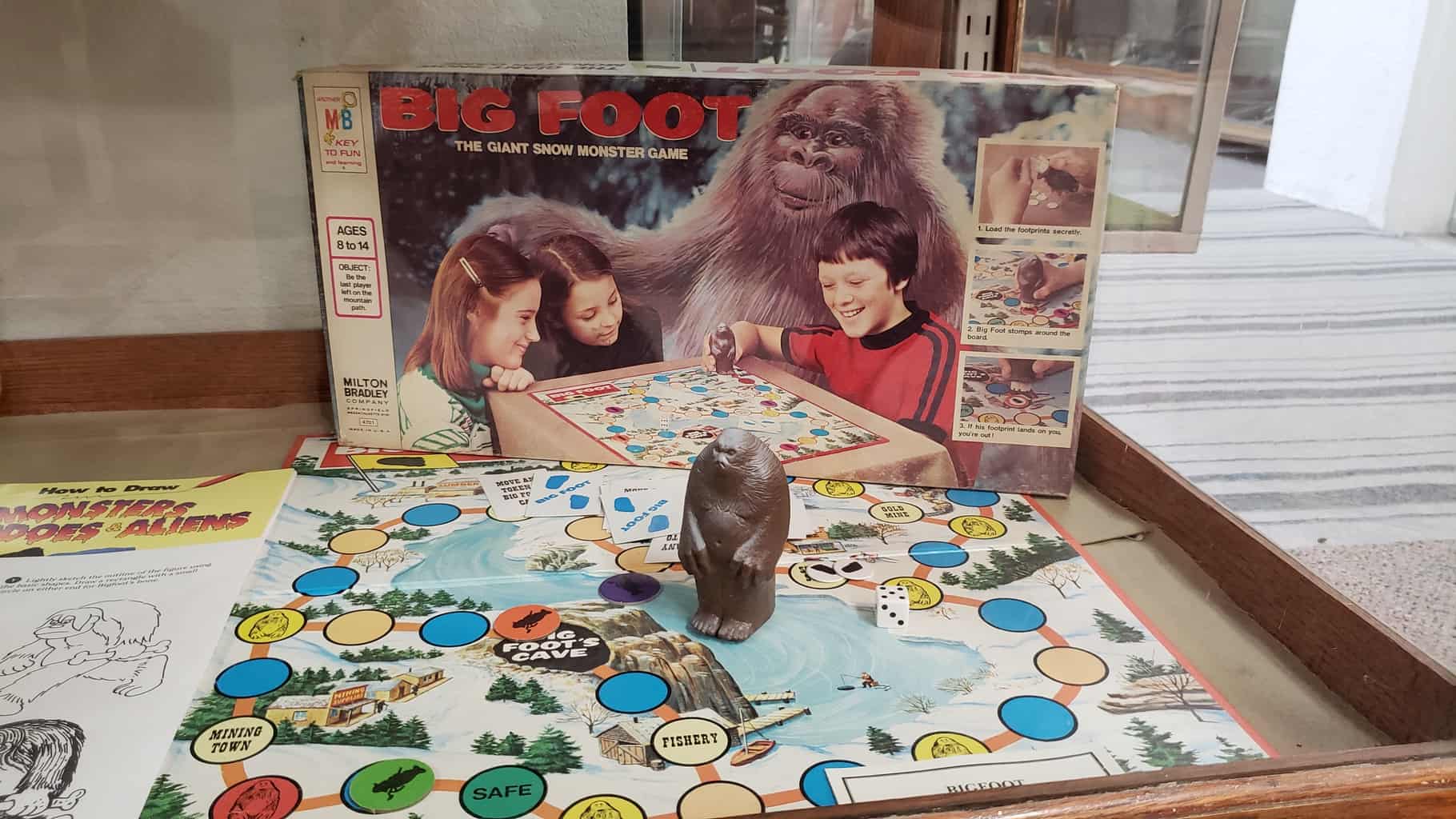

In the exhibit, there is a series of old newspaper clippings, including the original Jerry Crew papers; a blown-up image of Patty doing her famous walk through Bluff Creek; an old poster showing a map of locations where bigfoot were seen; a series of novels on mythical creatures; a vintage Bigfoot board game; an old RCA VHS camcorder (presumably used to record sightings of yore); and a plaster ashtray made in the shape of a Gigantopithecus mandible (one of the largest apes that ever lived), with credit to the original Bigfoot scientist, Grover Krantz.

There are also framed images of famous Bigfooters like Bob Titmus (the tracker who helped Crew cast his first print), journalist and author John Green, wildlife biologist John Bindernagel, and Idaho State anthropology professor Jeffrey Meldrum. There was even a framed letter addressed to Daryl Owen of the NorCal Squatchers, wherein someone by the name of Sterling Bunnell, M.D. reviewed hair samples that Owen had sent him. The verdict was that Bunnell couldn’t identify the animal, and that more tests needed to be done.

Outside of the exhibit, at the entrance to the museum, there were stacks of journals filled with Bigfoot stories from visitors. Some were descriptions of encounters with the creature or its prints, and others were diary-like musings on the creature’s possible existence.

Chastain spends a chunk of her time talking with a lot of these visitors, steeped in Bigfoot history while peddling books, magnets, t-shirts, and other souvenirs. So I asked her whether she bought the idea that Bigfoot is real.

“I did not believe in Bigfoot when I first started to work here. I just kind of was, eh, okay, maybe. But [after] talking to people …. I have come to believe that there truly is something out there and we’ve named him Bigfoot. Whatever he is. Or she,” Chastain said. “I think we need to believe in just about anything, because there are a lot of things out there that we have no idea about.”

I asked her what it was like to spend time in Willow Creek, a place where she’s lived on and off for the past 70 years. Chastain said that in the past it was a great place to live. But recently, it’s gone downhill.

“Now it’s pretty much just tourism and marijuana,” Chastain said.

Willow Creek used to be a friendly, safe place where everyone was interested in putting down roots, building up businesses, volunteering, and feeding the town’s economy, Chastain explained. But since weed was legalized, Willow Creek has taken on a new character, mostly because of the influx of weed trimmers or “trimmigrants”—all of whom seem uninterested in the welfare of the town.

“I voted for that law because they all [smoke weed] anyhow. But now I’m sorry that I did … None of them want to be a part of the community. All they want to do is make a bunch of money,” Chastain said. Their mere presence diminishes that innocent, small-town feel that inspires travelers to want to stop there, stay overnight at the motel, or grab a slice at the Pizza Factory, said Chastain.

Chastain isn’t the only one who feels that weed is impacting Willow Creek for the worse.

“Legalization ruined our culture here,” Grable told me the day before. Forests are being cleared to make room for cannabis farming and it’s destroying local nature, which Grable says is one of the most appealing aspects of living in Willow Creek.

“Humboldt County has earned the honorary title of ‘Weed Capital of the World,’” Grable said. “But people aren’t coming here for the weed. They’re here because it’s a beautiful place.”

It’s true: Soil erosion, stream diversion, haphazard grading and land clearing, and a steady stream of pesticides are murdering wildlife in Humboldt County, and there are no signs of it letting up.

“The cannabis revolution has changed our community by at least 50 percent populace-wise, land-use-wise, and age of our population,” said Steven Paine, a grey-haired, retired manager for the Willow Creek Community Services District, longtime member of the fire department, and former owner of several Willow Creek restaurants. When I met him, he had one of the warmest smiles I’d ever seen and wore one of the best American-flag button-ups on the face of the Earth.

“The death or the knell of logging in our country in the mid-80s drove many of our families away from employment opportunities,” Pain said, “and I think the cannabis revolution has done the rest of the work to change our community pretty permanently.”

As an outsider, I didn’t get the sense the town was totally overrun with riffraff or that it had lost its charm, though I did hear a few groups of 20-somethings talking about their “grows” over a set of BBQ and bacon cheeseburgers at Raging Creek (the rare restaurant in Willow Creek that isn’t named after Bigfoot). I also noticed a very dirty man talking to himself outside the local bar at 2pm, and quite a few “heroin chic” women stumbling around the grocery store while barefoot and half-dressed.

There aren’t that many businesses in general in Willow Creek, and they all keep odd hours. Because there’s no real competition, some establishments don’t even bother with the Bigfoot gimmick or any gimmick for that matter. The video store doesn’t even have a sign on it, and the local café is just called “Espresso.”

Personally, I thought the small-town feel was there, and I quickly got the sense that nothing too exciting ever happened. The first day I arrived, I introduced myself to a few people, and by the next morning almost everybody I spoke to said, “Ah, you’re the reporter. I expected to meet you.”

I wonder if the FBI honed their espionage tactics from observing Willow Creek natives.

Monday, September 3, 2018

9:00pm

I think what I like most about Willow Creek is that most of the people who live there don’t appear to care what anyone thinks of them. They seemed comfortable exposing everything about themselves: their histories, their beliefs, even their bodies.

Like yesterday, I went “Bigfoot Rafting”—which should have been called “Your Normal, Average Rafting Experience with the Word ‘Bigfoot’ on the Side of the Raft”—and we saw an old naked guy just free-balling by the water, to which our guide said, “Oh. Yeah. Him. Eh, he puts his clothes on when the kids come out to play. So nobody cares … There’s a lot of weird people here.”

Steven Streufert, Bigfoot researcher and Willow Creek’s new unofficial town historian since Hodgson’s passing, is a great example of a guy who doesn’t care what people think—ruthless in the pursuit of truth.

I met up with him inside his store Bigfoot Books, where it seems like you can buy every Sasquatch book known to man or animal—but you can also enjoy plenty of other non-Bigfoot titles. The store gets so little foot traffic that he keeps odd hours, showing up only for Bigfoot researchers and curious reporters such as myself who asked around town for his phone number and called him on a whim.

Streufert sported a beard, grey long-sleeved shirt and backwards ascot cap. He was very cool and well-spoken with the air of a professor who’s been teaching too long, seeming jaded because he knows too much, yet disappointed by how much the world still doesn’t know.

A self-described skeptic, Streufert moved to Willow Creek two decades ago with a belief that Bigfoot could be real. His enthusiasm for the subject led him and some friends to form the Bluff Creek Project (BCP) in 2009—an independent, open source, crowdfunded group interested in locating the original Patterson-Gimlin film site, which has become overgrown (they succeeded). They also set up motion-sensitive cameras around the area to catch footage of wildlife, and they review said footage every spring to see if they’ve captured a Bigfoot.

But after almost a decade of seeing no solid evidence of the creature, Streufert is less convinced of its legitimacy, and doesn’t care who knows it.

“I don’t accept any [evidence or claims] as de facto. Is there any good evidence? Well, I used to think so. But each piece of it falls apart. Either it’s inconclusive, which you can’t blame anyone for, or it’s really a hoax,” Streufert said. “Sometimes I just have to laugh because I live in the woods, and the crap that [some] claim as an encounter is something that happens in my yard every night. Howls, raccoons, eye-shine coming from deer.”

Over time, the BCP has become less involved with Bigfoot and more with general wildlife observation, sharing their data and photos with established groups like the Environmental Protection Information Center of Northern California and the Center for Biological Diversity. Although they’ve never photographed Bigfoot, the group has captured images of rare species like the Humboldt marten, a candidate for endangered species status.

Bigfoot shouldn’t get all the publicity in Willow Creek, according to Streufert.

“Breaking news can be the Bluff Creek Project documenting an endangered species while looking for Bigfoot,” Streufert said. “I think that’s a major achievement for research. That we actually found something real.”

Like me, Streufert isn’t a Bigfoot believer, but he believes in the possibility of Bigfoot’s existence and is fascinated by the impact it’s had on our culture.

“Even if it isn’t real, it’s still a fascinating topic … Even if it is just completely a matter of human psychology or modern urban legend, it’s worthy of study,” Streufert said. “It means a lot to certain people, obviously, because look at how many journalists have come here and contacted me in the last week. I mean, it’s crazy. What the heck is going on? Why do so many people care so much about [Sasquatch]?”

It’s a question I’ve been ruminating on since I arrived.

This whole time I’ve been talking about Bigfoot researchers and believers as if I’m an outsider looking in. But even though I’m a visitor to Willow Creek, there’s no denying that Bigfoot has taken up residence in my mind. I’m engrossed by the thought of a creature that may not exist and enraptured by others who feel the same. I thought I wanted to get into the heads of Squatchers—but maybe it’s my own secrets that I’m hoping to find.

That, I’ll buy.